I have given a few talks where I describe product management as (despite what some commentators might have you believe) a “uniquely hard job”. This might not be a fashionable opinion after the (much misunderstood) AirBnB repurposing of the PM role, but I stand behind the assertion.

The problem with saying that any job is “hard” is that people who do different jobs think that you’re saying that their job is easy. But “jobs being hard” is not a zero-sum game and it’s quite possible for us all to have hard jobs. There’s a strong iceberg effect that affects all of us, where we look at someone’s job from afar and judge their entire worth on what we see, ignoring all the stuff that we don’t see. This is natural, but it doesn’t do anyone any favours.

In any case, there are two distinct ways that product management can be hard. We might consider these in terms of the “bad product manager” and “good product manager” from the classic Ben Horowitz post. As an aside, I do have issues with the concept of people being inherently good or bad at anything. I certainly can’t disagree with many of the activities in that article being hallmarks of poorly performing product teams, but so much of this feels like a system failure rather than people being personally good or bad at their jobs.

If a well-functioning company is hiring “bad product managers” then this represents a hiring process problem that the company’s leadership team needs to address. Let’s assume a few people will sneak their way in anyway, but that shouldn’t be the norm. Which leads to…

If a well-functioning company tolerates “bad product managers” then this represents a problem with performance management that the company’s leadership needs to address. Either the product managers need to be coached to be better-performing product managers, or maybe it’s not going to work out. No one wants to have that discussion, but it usually ends up being better for everyone.

If a less-well-functioning company hires or tolerates “bad product managers”, does it actually think they’re bad, or are they doing exactly what is asked of them? Are they penalised for trying to be “good product managers”?

We mustn’t diminish the power that product managers have to self-actualise and to ensure they make the best of what they’ve got. But, there’s a lot of responsibility for leadership teams to enable operational excellence - it’s not all about “bad product managers” trying to be bad.

Anyway, for the sake of argument, let’s accept that there are “good” and “bad” product managers. Neither of them has it easy. Let’s dig into why, and how we might make it less hard.

It was the worst of Product Managers…

The scenario:

Product managers are seen as glorified message handlers that can translate business-speak to techie-speak and back again. They’re spending all of their time writing up tickets, 8-page long “one-pagers”, running coordination calls and generally project managing the ideas of the company’s founders and its sales team. They’re seen as an “internal function” and very much a cost centre. The PMs have no real idea about where their product is headed, or a solid grasp of anything outside of the delivery of said ideas.

Worse still, there are a million and one books and blog posts out there explaining in minute detail how everything they’re doing is wrong. They think they’re “bad product managers” because some old article says so. They’re getting blamed by their stakeholders within their company, whilst simultaneously being undercut and worked around at every opportunity.

How to make it better:

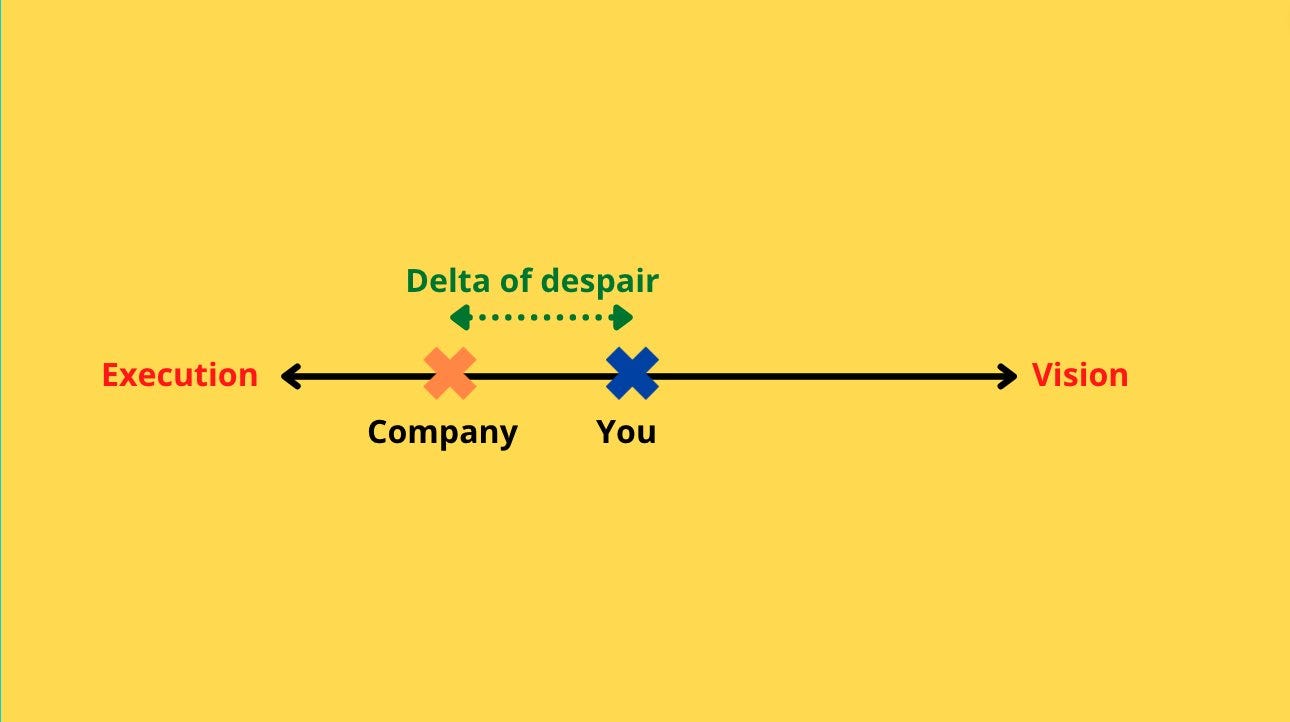

Without wanting to be defeatist, sometimes you don’t. But, that might be OK. You don’t have to work like any of these books! However, it’s important to look at yourself, your contribution, and whether you’re doing what you want to be doing. I’ve talked before about the “delta of despair” - the difference between how you’re working now and how you want to work ideally. Maybe you don’t get all the way there, but how can you reduce the distance?

Some concrete actions:

Work out if anyone else thinks there’s a problem, or if this is actually how you’re expected to work. It’s quite possible for a company to get to a certain level of success without doing anything by the book. Good for them! But, if you want to be doing certain things that you’re actively being blocked from doing, you should do something about that.

At the same time, work out if you think there’s a problem. Maybe you don’t actually want to do any of that messy strategy stuff. Maybe you’re quite happy executing someone else’s ideas and contributing what you can here and there. There’s no right or wrong. Work out what you want.

If there’s an appetite to change from both sides, start to be the change. An exercise I like to do with delivery-focused product managers is to ask them to project forward 3 years. What does the product look like in 3 years’ time? Do you have any idea? If not, how far ahead can you see? What do you need to see ahead further? What activities do you need to undertake to solve that problem? Start carving time out for those!

In the meantime, you’re still going to be getting told what to do, what to build. I remember talking to

, who famously coined the term “feature factory” about this on my podcast, and he has some excellent advice that I also recommend: Even if you’re told to do stuff, work backwards to what the plan would have been. You still build the thing, but you start to get used to building evidence-backed business cases for initiatives.Make sure that delivery is a shared burden. In the worst-performing teams I’ve worked with, the PMs were bottlenecks and expected to be there for every decision and to be herding everything over the line. This is one way to go, but in the best-performing teams, it’s always been a shared responsibility. This opens up time for you to start concentrating on some of the areas you’ve been neglecting.

There are obviously lots of situational, contextual thinking to be done, and it’s not simple. You need to get comfortable with marginal gains. It’s a long game, but maybe one day you’ll call yourself… a good product manager.

It was the best of Product Managers…

Ah, the “good product managers”, sitting there in their perfectly empowered product organisations, every company a unicorn and no disagreements with anyone. What could go wrong?

The scenario:

The PMs are making all the right moves, but they’re exhausted. Marty Cagan famously said that product managers often end up working 60-hour weeks. Marty has been lambasted from certain quarters about this, which I think is unfair since he never claimed that was a good thing or an aspiration. But, in any case, being a “good product manager” is exhausting. Why? Well, it’s the 2D zoom problem, of course.

Any type of product manager is constantly context-switching. As a “good” product manager, with deep involvement in strategy and consciousness of the whole product rather than just bits and pieces of delivery, you’re constantly zooming in and out from up in the strategic clouds all the way down to excruciatingly specific details.

You’re also code-switching in-between every conversation. You’re bouncing from Sales to Marketing to Customer Success to Support to Development to Data Science. You’re speaking to users and customers of your product. These groups have their own motivations, and indeed their own vocabulary. You have to be conversant in all of them and be able to switch in a heartbeat. The cognitive load is incredibly high, and there’s always too much to do.

How to make it better:

You’ve already got it better than the “bad product managers” that are slaving away reordering their backlogs for the 19th time this week, but it’s still not easy. Your job here is to try to reduce some of the cognitive load and make sure you can navigate all of this context-switching without driving yourself mad.

Some concrete actions:

Sharpen your storytelling - you need to be able to craft a story in as general terms as you can muster. Something that will resonate, in broad terms, with anyone who listens to it.

Develop your spoken communication - there’s a good book called The First Minute, which talks about how to get to the point and make sure you don’t string people along with irrelevant details. It’s very common for people acquainted with the minutiae of an initiative to spend way too explaining everything in excruciating detail. Get to the point and save your time and theirs.

Turn your discovery lens onto your colleagues. I often say that we PMs spend all of their time complaining they don’t get enough time to build empathy with their users whilst simultaneously refusing to build empathy with their colleagues. You need to know their motivations, what’s on their mind, and what’s coming down the pipe.

As with the previous example, make sure that your teams are doing their share so that you have time to concentrate on being a “good product manager”. It’s important to be helpful, but avoid the temptation to get stuck into things as soon as anything comes up. There’s a lot of talk about product managers being “glue”, or the lender of last resort when it comes to getting stuff done. I’m definitely not advocating letting things slide or abrogating responsibility for your product, but maybe don't be the first person to volunteer for something.

Make sure you spend your time on the most high-leverage tasks, the things that require things that only you can do. Don’t be afraid to delegate items that are busy work or legitimately the responsibility of other teams. This can be hard because many product managers love to be at the centre of everything, but every context you can avoid switching is probably a win.

So… why do we do this job again?

Whether it’s going well or poorly, product management is a hard job. There’s an incredibly high cognitive load and, in many companies, you’re getting shouted at by everyone else and you’re the one neck to wring. Why do we do this to ourselves?

Because our decisions can affect thousands, millions or billions of users. There are few things as rewarding as seeing someone get excited when you demonstrate something that solves their pain or makes their lives better. There’s joy in tying together business, technology and design, and seeing a whole product come out the back. It’s hard work, and sometimes you’ll end up with asbestos dust in your hair but, whatever the product you’re working on, you can make a real difference.

Just tread carefully.

Other stuff

Here are some other bits and pieces I’ve either done myself or seen around the web. I’m trying to get better at remembering useful things I see, so I can share them with you!

I spoke to Deepa Goyal, Product Strategy Lead at Postman about all things API product management, what’s different and what’s the same. Check the episode out here.

I spoke to Daniel Stillman, conversation designer at The Conversation Factory about how we can foster psychological safety and rewire our Conversation OS. Check the episode out here.

I also contributed to Collato’s article, “How to Say No as a Product Manager”. Saying “no” as a PM is a bit of a cliché, and harder to do when confronted by big whale customers, but there are ways around it. Check out my, and many other people’s, advice on how to do it properly.

I’m getting diminishing returns from social media recently but Meta has released Threads - I’m there as @jasontheknight. I’m not convinced by it quite yet but, on a similar topic, here’s a detailed summary of the current state of play with text-based social media from

: The End of the Honest Internet.I was pondering about making an impact in job interviews recently and my former podcast guest

reminded me of her PEARL framework to make the best of your interview attempt.Speaking of job hunting, my recent podcast guest Erika Klics has lots of free content on her website.

I have a Remarkable 2 tablet, which is nice enough but was eye-wateringly expensive. I was devastated when the pen broke, but I was delighted to find out that much cheaper Kindle Scribe pens work just as well!

Thanks for reading! Please drop me a line if you have any comments or would like me to cover anything in future newsletters. If you find this remotely useful, I’d love you to share it with your friends.